PART I

STUDIES ON HYSTERIA (1893-1895)

PRELIMINARY COMMUNICATION (1893) - BREUER AND FREUD

ON THE PSYCHICAL MECHANISM OF HYSTERICAL PHENOMENA: PRELIMINARY COMMUNICATION (1893) - BREUER AND FREUD

A chance observation has led us, over a number of years, to investigate a great variety of different forms and symptoms of hysteria, with a view to discovering their precipitating cause - the event which provoked the first occurrence, often many years earlier, of the phenomenon in question. In the great majority of cases it is not possible to establish the point of origin by a simple interrogation of the patient, however thoroughly it may be carried out. This is in part because what is in question is often some experience which the patient dislikes discussing; but principally because he is genuinely unable to recollect it and often has no suspicion of the causal connection between the precipitating event and the pathological phenomenon. As a rule it is necessary to hypnotize the patient and to arouse his memories under hypnosis of the time at which the symptom made its first appearance; when this has been done, it becomes possible to demonstrate the connection in the clearest and most convincing fashion.

This method of examination has in a large number of cases produced results which seem to be of value alike from a theoretical and a practical point of view.

They are valuable theoretically because they have taught us that external events determine the pathology of hysteria to an extent far greater than is known and recognized. It is of course obvious that in cases of ‘traumatic’ hysteria what provokes the symptoms is the accident. The causal connection is equally evident in hysterical attacks when it is possible to gather from the patient’s utterances that in each attack he is hallucinating the same event which provoked the first one. The situation is more obscure in the case of other phenomena.

Our experiences have shown us, however, that the most various symptoms, which are ostensibly spontaneous and, as one might say, idiopathic products of hysteria, are just as strictly related to the precipitating trauma as the phenomena to which we have just alluded and which exhibit the connection quite clearly. The symptoms which we have been able to trace back to precipitating factors of this sort include neuralgias and anaesthesias of very various kinds, many of which had persisted for years, contractures and paralyses, hysterical attacks and epileptic convulsions, which every observer regarded as true epilepsy, petit mal and disorders in the nature of tic, chronic vomiting and anorexia, carried to the pitch of rejection of all nourishment, various forms of disturbance of vision, constantly recurrent visual hallucinations, etc. The disproportion between the many years’ duration of the hysterical symptom and the single occurrence which provoked it is what we are accustomed invariably to find in traumatic neuroses.

Quite frequently it is some event in childhood that sets up a more or less severe symptom which persists during the years that follow.

The connection is often so clear that it is quite evident how it was that the precipitating event produced this particular phenomenon rather than any other. In that case the symptom has quite obviously been determined by the precipitating cause. We may take as a very commonplace instance a painful emotion arising during a meal but suppressed at the time, and the producing nausea and vomiting which persists for months in the form of hysterical vomiting. A girl, watching beside a sick-bed in a torment of anxiety, fell into a twilight state and had a terrifying hallucination, while her right arm, which was hanging over the back of the chair, went to sleep; from this there developed a paresis of the same arm accompanied by contracture and anaesthesia. She tried to pray but could find no words; a length she succeeded in repeating a children’s prayer in English. When subsequently a severe and highly complicated hysteria developed, she could only speak, write and understand English, while her native language remained unintelligible to her for eighteen months. - The mother of a very sick child, which had at last fallen asleep, concentrated her whole will-power on keeping still so as not to waken it. Precisely on account of her intention she made a ‘clacking’ noise with her tongue. (An instance of ‘hysterical counter-will’.) This noise was repeated on a subsequent occasion on which she wished to keep perfectly still; and from it there developed a tic which, in the form of a clacking with the tongue, occurred over a period of many years whenever she felt excited. - A highly intelligent man was present while his brother had an ankylosed hip-joint extended under an anaesthetic. At the instant at which the joint gave way with a crack, he felt a violent pain in his own hip-joint, which persisted for nearly a year. - Further instances could be quoted.

In other cases the connection is not so simple. It consists only in what might be called a ‘symbolic’ relation between the precipitating cause and the pathological phenomenon - a relation such as healthy people form in dreams. For instance, a neuralgia may follow upon mental pain or vomiting upon a feeling of moral disgust. We have studied patients who used to make the most copious use of this sort of symbolization. In still other cases it is not possible to understand at first sight how they can be determined in the manner we have suggested. It is precisely the typical hysterical symptoms which fall into this class, such as hemi-anaesthesia, contraction of the field of vision, epileptiform convulsions, and so on. An explanation of our views on this group must be reserved for a fuller discussion of the subject.

Observations such as these seem to us to establish an analogy between the pathogenesis of common hysteria and that of the traumatic neuroses, and to justify an extension of the concept of traumatic hysteria. In traumatic neuroses the operative cause of the illness is not the trifling physical injury but the affect of fright - the psychical trauma. In an analogous manner, our investigations reveal, for many, if not for most, hysterical symptoms, precipitating causes which can only be described as psychical traumas. Any experience which calls up distressing affects - such as those of fright, anxiety, shame or physical pain - may operate as a trauma of this kind; and whether it in fact does so depends naturally enough on the susceptibility of the person affected (as well as on another condition which will be mentioned later). In the case of common hysteria it not infrequently happens that, instead of a single, major trauma, we find a number of partial traumas forming a group of provoking causes. These have only been able to exercise a traumatic effect by summation and they belong together in so far as they are in part components of a single story of suffering. There are other cases in which an apparently trivial circumstance combines with the actually operative event or occurs at a time of peculiar susceptibility to stimulation and in this way attains the dignity of a trauma which it would not otherwise have possessed but which thenceforward persists.

But the causal relation between the determining psychical trauma and the hysterical phenomenon is not of a kind implying that the trauma merely acts like an agent provocateur in releasing the symptom, which thereafter leads an independent existence. We must presume rather that the psychical trauma - or more precisely the memory of the trauma - acts like a foreign body which long after its entry must continue to be regarded as an agent that is still at work; and we find the evidence for this in a highly remarkable phenomenon which at the same time lends an important practical interest to our findings.

For we found, to our great surprise at first, that each individual hysterical symptom immediately and permanently disappeared when we had succeeded in bringing clearly to light the memory of the event by which it was provoked and in arousing its accompanying affect, and when the patient had described that event in the greatest possible detail and had put the affect into words. Recollection without affect almost invariably produces no result. The psychical process which originally took place must be repeated as vividly as possible; it must be brought back to its status nascendi and then given verbal utterance. Where what we are dealing with are phenomena involving stimuli (spasms, neuralgias and hallucinations) these re-appear once again with the fullest intensity and then vanish for ever. Failures of function, such as paralyses and anaesthesias, vanish in the same way, though, of course, without the temporary intensification being discernible.¹

¹ The possibility of a therapeutic procedure of this kind has been clearly recognized by Delboeuf and Binet, as is shown by the following quotations : 'On s’expliquerait dès lors comment le magnétiseur aide à la guérison. Il remet le sujet dans l’état où le mal s’est manifesté et combat par la parole le même mal, mais renaissant.’ [‘We can now explain how the hypnotist promotes cure. He puts the subject back into the state in which his trouble first appeared and uses words to combat that trouble, as it now makes a fresh emergence.’] (Delboeuf 1889.) - ‘. . . peut-être verra-t-on qu’en reportant le malade par un artifice mental au moment même où le symptôme a apparu pour la première fois, on rend ce malade plus docile à une suggestion curative.’ [‘. . . we shall perhaps find that by taking the patient back by mean of a mental artifice to the very moment at which the symptom first appeared, we may make him more susceptible to a therapeutic suggestion.’] (Binet, 1892, 243.) - In Janet’s interesting study on mental automatism (1889), there is an account of the cure of a hysterical girl by a method analogous to ours.

It is plausible to suppose that it is a question here of unconscious suggestion: the patient expects to be relieved of his sufferings by this procedure, and it is this expectation, and not the verbal utterance, which is the operative factor. This, however, is not so. The first case of this kind that came under observation dates back to the year 1881, that is to say to the ‘pre-suggestion’ era. A highly complicated case of hysteria was analysed in this way, and the symptoms, which sprang from separate causes, were separately removed.

This observation was made possible by spontaneous auto-hypnoses on the part of the patient, and came as a great surprise to the observer.

We may reverse the dictum ‘cessante causa cessat effectuss’ [‘when the cause ceases the effect ceases’] and conclude from these observations that the determining process continues to operate in some way or other for years - not indirectly, through a chain of intermediate causal links, but as a directly releasing cause just as a psychical pain that is remembered in waking consciousness still provokes a lachrymal secretion long after the event. Hysterics suffer mainly from reminiscences.¹

¹ In this preliminary communication it is not possible for us to distinguish what is new in it from what has been said by other authors such as Moebius and Strümpell who have held similar views on hysteria to ours. We have found the nearest approach to what we have to say on the theoretical and therapeutic sides of the question in some remarks, published from time to time, by Benedikt. These we shall deal with elsewhere.

II

At first sight it seems extraordinary that events experienced so long ago should continue to operate so intensely - that their recollection should not be liable to the wearing away process to which, after all, we see all our memories succumb. The following considerations may perhaps make this a little more intelligible.

The fading of a memory or the losing of its affect depends on various factors. The most important of these is whether there has been an energetic reaction to the event that provokes the affect. By ‘reaction’ we here understand the whole class of voluntary and involuntary reflexes - from tears to acts of revenge - in which, as experience shows us, the affects are discharged. If this reaction takes place to a sufficient amount a large part of the affect disappears as a result. Linguistic usage bears witness to this fact of daily observation by such phrases as ‘to cry oneself out’ [‘sich ausweinen’], and to ‘blow off steam’ [‘sich austoben’, literally ‘to rage oneself out’]. If the reaction is suppressed, the affect remains attached to the memory. An injury that has been repaid, even if only in words, is recollected quite differently from one that has had to be accepted. Language recognizes this distinction, too, in its mental and physical consequences; it very characteristically describes an injury that has been suffered in silence as ‘a mortification’ [‘Kränkung’, literally ‘making ill’]. - The injured person’s reaction to the trauma only exercises a completely ‘cathartic’ effect if it is an adequate reaction - as, for instance, revenge. But language serves as a substitute for action; by its help, an affect can be ‘abreacted’ almost as effectively. In other cases speaking is itself the adequate reflex, when, for instance, it is a lamentation or giving utterance to a tormenting secret, e.g. a confession. If there is no such reaction, whether in deeds or words, or in the mildest cases in tears, any recollection of the event retains its affective tone to begin with.

'Abreaction’, however, is not the only method of dealing with the situation that is open to a normal person who has experienced a psychical trauma. A memory of such a trauma, even if it has not been abreacted, enters the great complex of associations, it comes alongside other experiences, which may contradict it, and is subjected to rectification by other ideas. After an accident, for instance, the memory of the danger and the (mitigated) repetition of the fright becomes associated with the memory of what happened afterwards - rescue and the consciousness of present safety. Again, a person’s memory of a humiliation is corrected by his putting the facts right, by considering his own worth, etc. In this way a normal person is able to bring about the disappearance of the accompanying affect through the process of association.

To this we must add the general effacement of impressions, the fading of memories which we name ‘forgetting’ and which wears away those ideas in particular that are no longer affectively operative.

Our observations have shown, on the other hand, that the memories which have become the determinants of hysterical phenomena persist for a long time with astonishing freshness and with the whole of their affective colouring. We must, however, mention another remarkable fact, which we shall later be able to turn to account, namely, that these memories, unlike other memories of their past lives, are not at the patients’ disposal. On the contrary, these experiences are completely absent from the patient’s memory when they are in a normal psychical state, or are only present in highly summary form. Not until they have been questioned under hypnosis do these memories emerge with the undiminished vividness of a recent event.

Thus, for six whole months, one of our patients reproduced under hypnosis with hallucinatory vividness everything that had excited her on the same day of the previous year (during an attack of acute hysteria). A diary kept by her mother with out her knowledge proved the completeness of the reproduction. Another patient, partly under hypnosis and partly during spontaneous attacks, re-lived with hallucinatory clarity all the events of a hysterical psychosis which she had passed through ten years earlier and which she had for the most part forgotten till the moment at which it re-emerged. Moreover, certain memories of aetiological importance which dated back from fifteen to twenty-five years were found to be astonishingly intact and to possess remarkable sensory force, and when they returned they acted with all the affective strength of new experiences.

This can only be explained on the view that these memories constitute an exception in their relation to all the wearing-away processes which we have discussed above. It appears, that is to say, that these memories correspond to traumas that have not been sufficiently abreacted; and if we enter more closely into the reasons which have prevented this, we find at least two sets of conditions under which the reaction to the trauma fails to occur.

In the first group are those cases in which the patients have not reacted to a psychical trauma because the nature of the trauma excluded a reaction, as in the case of the apparently irreparable loss of a loved person or because social circumstance made a reaction impossible or because it was a question of things which the patient wished to forget, and therefore intentionally repressed from his conscious thought and inhibited and suppressed. It is precisely distressing things of this kind that, under hypnosis, we find are the basis of hysterical phenomena (e.g. hysterical deliria in saints and nuns, continent women and well- brought-up children).

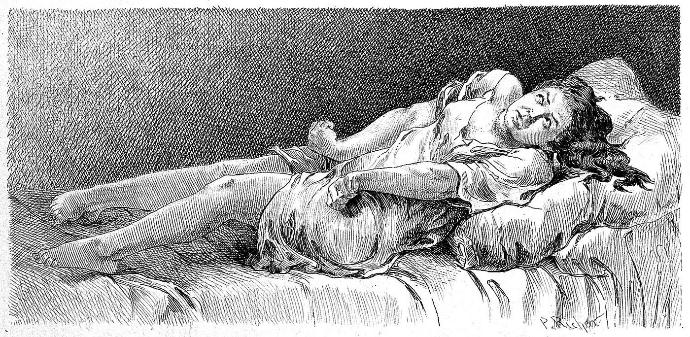

The second group of conditions are determined, not by the content of the memories but by the psychical states in which the patient received the experiences in question. For we find, under hypnosis, among the causes of hysterical symptoms ideas which are not in themselves significant, but whose persistence is due to the fact that they originated during the prevalence of severely paralysing affects, such as fright, or during positively abnormal psychical states, such as the semi-hypnotic twilight state of day-dreaming, auto- hypnoses, and so on. In such cases it is the nature of the states which makes a reaction to the event impossible.

Both kinds of conditions may, of course, be simultaneously present, and this, in fact, often occurs. It is so when a trauma which is operative in itself takes place while a severely paralysing affect prevails or during a modified state of consciousness. But it also seems to be true that in many people a psychical trauma produces one of these abnormal states, which, in turn, makes reaction impossible.

Both of these groups of conditions, however, have in common the fact that the psychical traumas which have not been disposed of by reaction cannot be disposed of either by being worked over by means of association. In the first group the patient is determined to forget the distressing experiences and accordingly excludes them so far as possible from association; while in the second group the associative working-over fails to occur because there is no extensive associative connection between the normal state of consciousness and the pathological ones in which the ideas made their appearance. We shall have occasion immediately to enter further into this matter.

It may therefore be said that the ideas which have become pathological have persisted with such freshness and affective strength because they have been denied the normal wearing-away process by means of abreaction and reproduction in states of uninhibited association.

III

We have stated the conditions which, as our experience shows, are responsible for the development of hysterical phenomena from psychical traumas. In so doing, we have already been obliged to speak of abnormal states of consciousness in which these pathogenic ideas arise, and to emphasize the fact that the recollection of the operative psychical trauma is not to be found in the patient’s normal memory but in his memory when he is hypnotized. The longer we have been occupied with these phenomena the more we have become convinced that the splitting of consciousness which is so striking in the well-known classical cases under the form of ‘double conscience’ is present to a rudimentary degree in every hysteria, and that a tendency to such dissociation, and with it the emergence of abnormal states of consciousness (which we shall bring together under the term ‘hypnoid’) is the basic phenomenon of this neurosis. In these views we concur with Binet and the two Janets, though we have had no experience of the remarkable findings they have made on anaesthetic patients.

We should like to balance the familiar thesis that hypnosis is an artificial hysteria by another - the basis and sine qua non of hysteria is the existence of hypnoid states. These states share with one another and with hypnosis, however much they may differ in other respects, one common feature: the ideas which emerge in them are very intense but are cut off from associative communication with the rest of the content of consciousness. Associations may take place between these hypnoid states, and their ideational content can in this way reach a more or less high degree of psychical organization. Moreover, the nature of these states and the extent to which they are cut off from the remaining conscious processes must be supposed to vary just as happens in hypnosis, which ranges from a light drowsiness to somnambulism, from complete recollection to total amnesia.

If hypnoid states of this kind are already present before the onset of the manifest illness, they provide the soil in which the affect plants the pathogenic memory with its consequent somatic phenomena. This corresponds to dispositional hysteria. We have found, however, that a severe trauma (such as occurs in a traumatic neurosis) or a laborious suppression (as of a sexual affect, for instance) can bring about a splitting-off of groups of ideas even in people who are in other respects unaffected; and this would be the mechanism of psychically acquired hysteria. Between the extremes of these two forms we must assume the existence of a series of cases within which the liability to dissociation in the subject and the affective magnitude of the trauma vary inversely.

We have nothing new to say on the question of the origin of these dispositional hypnoid states. They often, it would seem, grow out of the day-dreams which are so common even in healthy people and to which needlework and similar occupations render women especially prone. Why it is that the ‘pathological associations’ brought about in these states are so stable and why they have so much more influence on somatic processes than ideas are usually found to do - these questions coincide with the general problem of the effectiveness of hypnotic suggestions. Our observations contribute nothing fresh on this subject. But they throw a light on the contradiction between the dictum ‘hysteria is a psychosis’ and the fact that among hysterics may be found people of the clearest intellect, strongest will, greatest character and highest critical power. This characterization holds good of their waking thoughts; but in their hypnoid states they are insane, as we all are in dreams. Whereas, however, our dream-psychoses have no effect upon our waking state, the products of hypnoid states intrude into waking life in the form of hysterical symptoms.

IV

What we have asserted of chronic hysterical symptoms can be applied almost completely to hysterical attacks. Charcot, as is well known, has given us a schematic description of the ‘major’ hysterical attack, according to which four phases can be distinguished in a complete attack: (1) the epileptoid phase, (2) the phase of large movements, (3) the phase of ‘attitudes passionelles’ (the hallucinatory phase), and (4) the phase of terminal delirium. Charcot derives all those forms of hysterical attack which are in practice met with more often than the complete ‘grande attaque’, from the abbreviation, absence or isolation of these four distinct phases.

Our attempted explanation takes its start from the third of these phases, that of the ‘attitudes passionelles’. Where this is present in a well-marked form, it exhibits the hallucinatory reproduction of a memory which was of importance in bringing about the onset of the hysteria - the memory either of a single major trauma (which we find par excellence in what is called traumatic hysteria) or of a series of interconnected part-traumas (such as underlie common hysteria). Or, lastly, the attack may revive the events which have become emphasized owing to their coinciding with a moment of special disposition to trauma.

There are also attacks, however, which appear to consist exclusively of motor phenomena and in which the phase of attitudes passionelles is absent. If one can succeed in getting into rapport with the patient during an attack such as this of generalized clonic spasms or cataleptic rigidity, or during an attaque de somneil [attack of sleep] - or if, better still, one can succeed in provoking the attack under hypnosis - one finds that here, too, there is an underlying memory of the psychical trauma or series of traumas, which usually comes to our notice in a hallucinatory phase.

Thus, a little girl suffered for years from attacks of general convulsions which could well be, and indeed were, regarded as epileptic. She was hypnotized with a view to a differential diagnosis, and promptly had one of her attacks. She was asked what, she was seeing and replied 'The dog! the dog’s coming!’; and in fact it turned out that she had had the first of her attacks after being chased by a savage dog. The success of the treatment confirmed the choice of diagnosis.

Again, an employee who had become a hysteric as a result of being ill-treated by his superior, suffered from attacks in which he collapsed and fell into a frenzy of rage, but without uttering a word or giving any sign of a hallucination. It was possible to provoke an attack under hypnosis, and the patient then revealed that he was living through the scene in which his employer had abused him in the street and hit him with a stick. A few days later the patient came back and complained of having had another attack of the same kind. On this occasion it turned out under hypnosis that he had been re-living the scene to which the actual onset of the illness was related: the scene in the law-court when he failed to obtain satisfaction for his maltreatment.

In all other respects, too, the memories which emerge, or can be aroused, in hysterical attacks correspond to the precipitating causes which we have found at the root of chronic hysterical symptoms. Like these latter causes, the memories underlying hysterical attacks relate to psychical traumas which have not been disposed of by abreaction or by associative thought activity. Like them, they are, whether completely or in essential elements, out of reach of the memory of normal consciousness and are found to belong to the ideational content of hypnoid states of consciousness with restricted association. Finally, too, the therapeutic test can be applied to them. Our observations have often taught us that a memory of this kind which has hitherto provoked attacks, ceases to be able to do so after the process of reaction and associative correction have been applied to it under hypnosis.

The motor phenomena of hysterical attacks can be interpreted partly as universal forms of reaction appropriate to the affect accompanying the memory (such as kicking about and waving the arms and legs, which even young babies do), partly as a direct expression of these memories; but in part, like the hysterical stigmata found among the chronic symptoms, they cannot be explained in this way.

Hysterical attacks, furthermore, appear in a specially interesting light if we bear in mind a theory that we have mentioned above, namely, that in hysteria groups of ideas originating in hypnoid states are present and that these are cut off from associative connection with the other ideas, but can be associated among themselves, and thus form the more or less highly organized rudiment of a second consciousness, a condition seconde. If this is so, a chronic hysterical symptom will correspond to the intrusion of this second state into the somatic innervation which is as a rule under the control of normal consciousness. A hysterical attack, on the other hand, is evidence of a higher organization of this second state. When the attack makes its first appearance, it indicates a moment at which this hypnoid consciousness has obtained control of the subject’s whole existence - it points, that is, to an acute hysteria; when it occurs on subsequent occasions and contains a memory it points to a return of that moment. Charcot has already suggested that hysterical attacks are a rudimentary form of a condition seconde. During the attack, control over the whole of the somatic innervation passes over to the hypnoid consciousness. Normal consciousness, as well-known observations show, is not always entirely repressed. It may even be aware of the motor phenomena of the attack, while the accompanying psychical events are outside its knowledge.

The typical course of a severe case of hysteria is, as we know, as follows. To begin with, an ideational content is formed during hypnoid states; when this has increased to a sufficient extent, it gains control, during a period of ‘acute hysteria’, of the somatic innervation and of the patient’s whole existence, and creates chronic symptoms and attacks; after this it clears up, apart from certain residues. If the normal personality can regain control, what is left over from the hypnoid ideational content recurs in hysterical attacks and puts the subject back from time to time into similar states, which are themselves once more open to influence and susceptible to traumas. A state of equilibrium, as it were, may then be established between the two psychical groups which are combined in the same person: hysterical attacks and normal life proceed side by side without interfering with each other. An attack will occur spontaneously, just as memories do in normal people; it is, however, possible to provoke one, just as any memory can be aroused in accordance with the laws of association. It can be provoked either by stimulation of a hysterogenic zone or by a new experience which sets it going owing to a similarity with the pathogenic experience. We hope to be able to show that these two kinds of determinant, though they appear to be so unlike, do not differ in essentials, but that in both a hyperaesthetic memory is touched on.

In other cases this equilibrium is very unstable. The attack makes its appearance as a manifestation of the residue of the hypnoid consciousness whenever the normal personality is exhausted and incapacitated. The possibility cannot be dismissed that here the attack may have been divested of its original meaning and may be recurring as a motor reaction without any content.

It must be left to further investigation to discover what it is that determines whether a hysterical personality manifests itself in attacks, in chronic symptoms or in a mixture of the two.

V

It will now be understood how it is that the psychotherapeutic procedure which we have described in these pages has a curative effect. It brings to an end the operative force of the idea which was not abreacted in the first instance, by allowing its strangulated affect to find a way out through speech; and it subjects it to associative correction by introducing it into normal consciousness (under light hypnosis) or by removing it through the physician’s suggestion, as it is done in somnambulism accompanied by amnesia.

In our opinion the therapeutic advantages of this procedure are considerable. It is of course true that we do not cure hysteria in so far as it is a matter of disposition. We can do nothing against the recurrence of hypnoid states. Moreover, during the productive stage of an acute hysteria our procedure cannot prevent the phenomena which have been so laboriously removed from being at once replaced by fresh ones. But once this acute stage is past, any residues which may be left in the form of chronic symptoms or attacks are often removed, and permanently so, by our method, because it is a radical one; in this respect it seems to us far superior in its efficacy to removal through direct suggestion, as it is practised to-day by psychotherapists.

If by uncovering the psychical mechanism of hysterical phenomena we have taken a step forward along the path first traced so successfully by Charcot with his explanation and artificial imitation of hystero- traumatic paralyses, we cannot conceal from ourselves that this has brought us nearer to an understanding only of the mechanism of hysterical symptoms and not of the internal causes of hysteria. We have done no more than touch upon the aetiology of hysteria and in fact have been able to throw light only on its acquired forms - on the bearing of accidental factors on the neurosis.

VIENNA, December 1892