PART II

STUDIES ON HYSTERIA (1893-1895)

PRELIMINARY COMMUNICATION (1893) - BREUER AND FREUD

ON THE PSYCHICAL MECHANISM OF HYSTERICAL PHENOMENA: PRELIMINARY COMMUNICATION (1893) - BREUER AND FREUD

FRÄULEIN ANNA O. (Breuer)

At the time of her falling ill (in 1880) Fräulein Anna O. was twenty-one years old. She may be regarded as having had a moderately severe neuropathic heredity, since some psychoses had occurred among her more distant relatives. Her parents were normal in this respect. She herself had hitherto been consistently healthy and had shown no signs of neurosis during her period of growth. She was markedly intelligent, with an astonishingly quick grasp of things and penetrating intuition. She possessed a powerful intellect which would have been capable of digesting solid mental pabulum and which stood in need of it - though without receiving it after she had left school. She had great poetic and imaginative gifts, which were under the control of a sharp and critical common sense. Owing to this latter quality she was completely unsuggestible; she was only influenced by arguments, never by mere assertions. Her willpower was energetic, tenacious and persistent; sometimes it reached the pitch of an obstinacy which only gave way out of kindness and regard for other people.

One of her essential character traits was sympathetic kindness. Even during her illness she herself was greatly assisted by being able to look after a number of poor, sick people, for she was thus able to satisfy a powerful instinct. Her states of feeling always tended to a slight exaggeration, alike of cheerfulness and gloom; hence she was sometimes subject to moods. The element of sexuality was astonishingly undeveloped in her. The patient, whose life became known to me to an extent to which one person’s life is seldom known to another, had never been in love; and in all the enormous number of hallucinations which occurred during her illness that element of mental life never emerged.

This girl, who was bubbling over with intellectual vitality, led an extremely monotonous existence in her puritanically-minded family. She embellished her life in a manner which probably influenced her decisively in the direction of her illness, by indulging in systematic day-dreaming, which she described as her ‘private theatre’. While everyone thought she was attending, she was living through fairy tales in her imagination; but she was always on the spot when she was spoken to, so that no one was aware of it. She pursued this activity almost continuously while she was engaged on her household duties, which she discharged unexceptionably. I shall presently have to describe the way in which this habitual day-dreaming while she was well passed over into illness without a break.

The course of the illness fell into several clearly separable phases:

(A) Latent incubation. From the middle of July, 1880, till about December 10. This phase of an illness is usually hidden from us; but in this case, owing to its peculiar character, it was completely accessible; and this in itself lends no small pathological interest to the history, I shall describe this phase presently.

(B) The manifest illness. A psychosis of a peculiar kind, paraphasia, a convergent squint, severe disturbances of vision, paralyses (in the form of contractures), complete in the right upper and both lower extremities, partial in the left upper extremity, paresis of the neck muscles. A gradual reduction of the contracture to the right-hand extremities. Some improvement, interrupted by a severe psychical trauma (the death of the patient’s father) in April, after which there followed

(C) A period of persisting somnambulism, subsequently alternating with more normal states. A number of chronic symptoms persisted till December, 1881.

(D) Gradual cessation of the pathological states and symptoms up to June, 1882.

In July, 1880, the patient’s father, of whom she was passionately fond, fell ill of a peripleuritic abscess which failed to clear up to which he succumbed in April, 1881. During the first months of the illness Anna devoted her whole energy to nursing her father, and no one was much surprised when by degrees her own health greatly deteriorated. No one, perhaps not even the patient herself, knew what was happening to her; but eventually the state of weakness, anaemia and distaste for food became so bad that to her great sorrow she was no longer allowed to continue nursing the patient. The immediate cause of this was a very severe cough, on account of which I examined her for the first time. It was a typical tussis nervosa. She soon began to display a marked craving for rest during the afternoon, followed in the evening by a sleep-like state and afterwards a highly excited condition.

At the beginning of December a convergent squint appeared. An ophthalmic surgeon explained this (mistakenly) as being due to paresis of one abducens. On December 11 the patient took to her bed and remained there until April 1.

There developed in rapid succession a series of severe disturbances which were apparently quite new: left-sided occipital headache; convergent squint (diplopia), markedly increased by excitement; complaints that the walls of the room seemed to be falling over (affection of the obliquus); disturbances of vision which it was hard to analyse; paresis of the muscles of the front of the neck, so that finally the patient could only move her head by pressing it backwards between her raised shoulders and moving her whole back; contracture and anaesthesia of the right upper, and, after a time, of the right lower extremity. The latter was fully extended, adducted and rotated inwards. Later the same symptom appeared in the left lower extremity and finally in the left arm, of which, however, the fingers to some extent retained the power of movement. So, too, there was no complete rigidity in the shoulder-joints. The contracture reached its maximum in the muscles of the upper arms. In the same way, the region of the elbows turned out to be the most affected by anaesthesia when, at a later stage, it became possible to make a more careful test of this. At the beginning of the illness the anaesthesia could not be efficiently tested, owing to the patient’s resistance arising from feelings of anxiety.

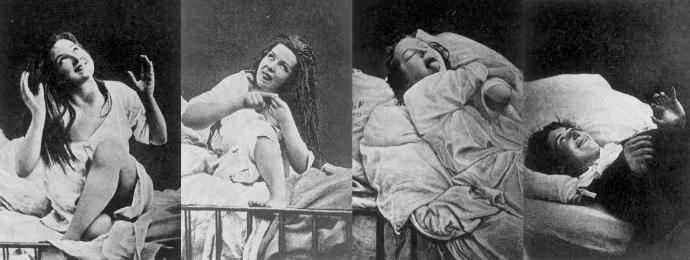

It was while the patient was in this condition that I under took her treatment, and I at once recognized the seriousness of the psychical disturbance with which I had to deal. Two entirely distinct states of consciousness were present which alternated very frequently and without warning and which became more and more differentiated in the course of the illness. In one of these states she recognized her surroundings; she was melancholy and anxious, but relatively normal. In the other state she hallucinated and was ‘naughty’ - that is to say, she was abusive, used to throw the cushions at people, so far as the contractures at various times allowed, tore buttons off her bed clothes and linen with those of her fingers which she could move, and so on. At this stage of her illness if something had been moved in the room or someone had entered or left it she would complain of having ‘lost’ some time and would remark upon the gap in her train of conscious thoughts. Since those about her tried to deny this and to soothe her when she complained that she was going mad, she would, after throwing the pillows about, accuse people of doing things to her and leaving her in a muddle, etc.

These ‘absences’ had already been observed before she took to her bed; she used then to stop in the middle of a sentence, repeat her last words and after a short pause go on talking. These interruptions gradually increased till they reached the dimensions that have just been described; and during the climax of the illness, when the contractures had extended to the left side of her body, it was only for a short time during the day that she was to any degree normal. But the disturbances invaded even her moments of relatively clear consciousness. There were extremely rapid changes of mood leading to excessive but quite temporary high spirits, and at other times severe anxiety, stubborn opposition to every therapeutic effort and frightening hallucinations of black snakes, which was how she saw her hair, ribbons and similar things. At the same time she kept on telling herself not to be so silly: what she was seeing was really only her hair, etc. At moments when her mind was quite clear she would complain of the profound darkness in her head, of not being able to think, of becoming blind and deaf, of having two selves, a real one and an evil one which forced her to behave badly, and so on.

In the afternoons she would fall into a somnolent state which lasted till about an hour after sunset. She would then wake up and complain that something was tormenting her - or rather, she would keep repeating in the impersonal form ‘tormenting, tormenting’. For alongside of the development of the contractures there appeared a deep-going functional disorganization of her speech. It first became noticeable that she was at a loss to find words, and this difficulty gradually increased. Later she lost her command of grammar and syntax; she no longer conjugated verbs, and eventually she used only infinitives, for the most part incorrectly formed from weak past participles; and she omitted both the definite and indefinite article. In the process of time she became almost completely deprived of words. She put them together laboriously out of four or five languages and became almost unintelligible. When she tried to write (until her contractures entirely prevented her doing so) she employed the same jargon. For two weeks she became completely dumb and in spite of making great and continuous efforts to speak she was unable to say a syllable. And now for the first time the psychical mechanism of the disorder became clear. As I knew, she had felt very much offended over something and had determined not to speak about it. When I guessed this and obliged her to talk about it, the inhibition, which had made any other kind of utterance impossible as well, disappeared.

This change coincided with a return of the power of movement to the extremities of the left side of her body, in March, 1881. Her paraphasia receded; but thenceforward she spoke only in English - apparently, however, without knowing that she was doing so. She had disputes with her nurse who was, of course, unable to understand her. It was only some months later that I was able to convince her that she was talking English. Nevertheless, she herself could still understand the people about her who talked German. Only in moments of extreme anxiety did her power of speech desert her entirely, or else she would use a mixture of all sorts of languages. At times when she was at her very best and most free, she talked French and Italian. There was complete amnesia between these times and those at which she talked English. At this point, too, her squint began to diminish and made its appearance only at moments of great excitement. She was once again able to support her head. On the first of April she got up for the first time.

On the fifth of April her adored father died. During her illness she had seen him very rarely and for short periods. This was the most severe psychical trauma that she could possibly have experienced. A violent outburst of excitement was succeeded by profound stupor which lasted about two days and from which she emerged in a greatly changed state. At first she was far quieter and her feelings of anxiety were much diminished. The contracture of her right arm and leg persisted as well as their anaesthesia, though this was not deep. There was a high degree of restriction of the field of vision: in a bunch of flowers which gave her much pleasure she could only see one flower at a time. She complained of not being able to recognize people. Normally, she said, she had been able to recognize faces without having to make any deliberate effort; now she was obliged to do laborious ‘recognizing work’¹ and had to say to herself ‘this person’s nose is such-and-such, his hair is such-and-such, so he must be so-and-so’. All the people she saw seemed like wax figures without any connection with her. She found the presence of some of her close relatives very distressing and this negative attitude grew continually stronger If someone whom she was ordinarily pleased to see came into the room, she would recognize him and would be aware of things for a short time, but would soon sink back into her own broodings and her visitor was blotted out. I was the only person whom she always recognized when I came in; so long as I was talking to her she was always in contact with things and lively, except for the sudden interruptions caused by one of her hallucinatory ‘absences’.

She now spoke only English and could not understand what was said to her in German. Those about her were obliged to talk to her in English; even the nurse learned to make herself to some extent understood in this way. She was, however, able to read French and Italian. If she had to read one of these aloud, what she produced, with extraordinary fluency, was an admirable extempore English translation.

She began writing again, but in a peculiar fashion. She wrote with her left hand, the less stiff one, and she used Roman printed letters, copying the alphabet from her edition of Shakespeare.

She had eaten extremely little previously, but now she refused nourishment altogether. However, she allowed me to feed her, so that she very soon began to take more food. But she never consented to eat bread. After her meal she invariably rinsed out her mouth and even did so if, for any reason, she had not eaten anything - which shows how absent-minded she was about such things.

¹ [In English in the original.]

Her somnolent states in the afternoon and her deep sleep after sunset persisted. If, after this, she had talked herself out (I shall have to explain what is meant by this later) she was clear in mind, calm and cheerful.

This comparatively tolerable state did not last long. Some ten days after her father’s death a consultant was brought in, whom, like all strangers, she completely ignored while I demonstrated all her peculiarities to him. ‘That’s like an examination,’¹ she said, laughing, when I got her to read a French text aloud in English. The other physician intervened in the conversation and tried to attract her attention, but in vain. It was a genuine ‘negative hallucination’ of the kind which has since so often been produced experimentally. In the end he succeeded in breaking through it by blowing smoke in her face. She suddenly saw a stranger before her, rushed to the door to take away the key and fell unconscious to the ground. There followed a short fit of anger and then a severe attack of anxiety which I had great difficulty in calming down. Unluckily I had to leave Vienna that evening, and when I came back several days later I found the patient much worse. She had gone entirely without food the whole time, was full of anxiety and her hallucinatory absences were filled with terrifying figures, death’s heads and skeletons. Since she acted these things through as though she was experiencing them and in part put them into words, the people around her became aware to a great extent of the content of these hallucinations.

The regular order of things was: the somnolent state in the afternoon, followed after sunset by the deep hypnosis for which she invented the technical name of ‘clouds’.² If during this she was able to narrate the hallucinations she had had in the course of the day, she would wake up clear in mind, calm and cheerful. She would sit down to work and write or draw far into the night quite rationally. At about four she would go to bed. Next day the whole series of events would be repeated. It was a truly remarkable contrast: in the day-time the irresponsible patient pursued by hallucinations, and at night the girl with her mind completely clear.

¹ [In English in the original.]

² [In English in the original.]

In spite of her euphoria at night, her psychical condition deteriorated steadily. Strong suicidal impulses appeared which made it seem inadvisable for her to continue living on the third floor. Against her will, therefore, she was transferred to a country house in the neighbourhood of Vienna (on June 7, 1881). I had never threatened her with this removal from her home, which she regarded with horror, but she herself had, without saying so, expected and dreaded it. This event made it clear once more how much the affect of anxiety dominated her psychical disorder. Just as after her father’s death a calmer condition had set in, so now, when what she feared had actually taken place, she once more became calmer. Nevertheless, the move was immediately followed by three days and nights completely without sleep or nourishment, by numerous attempts at suicide (though, so long as she was in a garden, these were not dangerous), by smashing windows and so on, and by hallucinations unaccompanied by absences which she was able to distinguish easily from her other hallucinations. After this she grew quieter, let the nurse feed her and even took chloral at night.

Before continuing my account of the case, I must go back once more and describe one of its peculiarities which I have hitherto mentioned only in passing. I have already said that throughout the illness up to this point the patient fell into a somnolent state every afternoon and that after sunset this period passed into a deeper sleep - ‘clouds’. (It seems plausible to attribute this regular sequence of events merely to her experience while she was nursing her father, which she had had to do for several months. During the nights she had watched by the patient’s bedside or had been awake anxiously listening till the morning; in the afternoons she had lain down for a short rest, as is the usual habit of nurses. This pattern of waking at night and sleeping in the afternoons seems to have been carried over into her own illness and to have persisted long after the sleep had been replaced by a hypnotic state.) After the deep sleep had lasted about an hour she grew restless, tossed to and fro and kept repeating ‘tormenting, tormenting’, with her eyes shut all the time. It was also noticed how, during her absences in day-time she was obviously creating some situation or episode to which she gave a clue with a few muttered words. It happened then - to begin with accidentally but later intentionally - that someone near her repeated one of these phrases of hers while she was complaining about the ‘tormenting’. She at once joined in and began to paint some situation or tell some story, hesitatingly at first and in her paraphasic jargon; but the longer she went on the more fluent she became, till at last she was speaking quite correct German. (This applies to the early period before she began talking English only.) The stories were always sad and some of them very charming, in the style of Hans Andersen’s Picture-book without Pictures, and, indeed, they were probably constructed on that model. As a rule their starting-point or central situation was of a girl anxiously sitting by a sick-bed. But she also built up her stories on quite other topics. - A few moments after she had finished her narrative she would wake up, obviously calmed down, or, as she called it, ‘gehäglich’.¹ During the night she would again become restless, and in the morning, after a couple of hours’ sleep, she was visibly involved in some other set of ideas. - If for any reason she was unable to tell me the story during her evening hypnosis she failed to calm down afterwards, and on the following day she had to tell me two stories in order for this to happen.

¹ [She used this made-up word instead of the regular German ‘behaglich’, meaning ‘comfortable’.]

The essential features of this phenomenon - the mounting up and intensification of her absences into her auto-hypnosis in the evening, the effect of the products of her imagination as psychical stimuli and the easing and removal of her state of stimulation when she gave utterance to them in her hypnosis - remained constant throughout the whole eighteen months during which she was under observation.

The stories naturally became still more tragic after her father’s death. It was not, however, until the deterioration of her mental condition, which followed when her state of somnambulism was forcibly broken into in the way already described, that her evening narratives ceased to have the character of more or less freely-created poetical compositions and changed into a string of frightful and terrifying hallucinations. (It was already possible to arrive at these from the patient’s behaviour during the day.) I have already described how completely her mind was relieved when, shaking with fear and horror, she had reproduced these frightful images and given verbal utterance to them.

While she was in the country, when I was unable to pay her daily visits, the situation developed as follows. I used to visit her in the evening, when I knew I should find her in her hypnosis, and I then relieved her of the whole stock of imaginative products which she had accumulated since my last visit. It was essential that this should be effected completely if good results were to follow. When this was done she became perfectly calm, and next day she would be agreeable, easy to manage, industrious and even cheerful; but on the second day she would be increasingly moody, contrary and unpleasant, and this would become still more marked on the third day. When she was like this it was not always easy to get her to talk, even in her hypnosis. She aptly described this procedure, speaking seriously, as a ‘talking cure’¹, while she referred to it jokingly as ‘chimney-sweeping’.¹ She knew that after she had given utterance to her hallucinations she would lose all her obstinacy and what she described as her ‘energy’; and when, after some comparatively long interval, she was in a bad temper, she would refuse to talk, and I was obliged to overcome her unwillingness by urging and pleading and using devices such as repeating a formula with which she was in the habit of introducing her stories. But she would never begin to talk until she had satisfied herself of my identity by carefully feeling my hands. On those nights on which she had not been calmed by verbal utterance it was necessary to fall back upon chloral. I had tried it on a few earlier occasions, but I was obliged to give her 5 grammes, and sleep was preceded by a state of intoxication which lasted for some hours. When I was present this state was euphoric, but in my absence it was highly disagreeable and characterized by anxiety as well as excitement. (It may be remarked incidentally that this severe state of intoxication made no difference to her contractures.) I had been able to avoid the use of narcotics, since the verbal utterance of her hallucinations calmed her even though it might not induce sleep; but when she was in the country the nights on which she had not obtained hypnotic relief were so unbearable that in spite of everything it was necessary to have recourse to chloral. But it became possible gradually to reduce the dose.

¹ [In English in the original.]

The persisting somnambulism did not return. But on the other hand the alternation between two states of consciousness persisted. She used to hallucinate in the middle of a conversation, run off, start climbing up a tree, etc. If one caught hold of her, she would very quickly take up her interrupted sentence without knowing anything about what had happened in the interval. All these hallucinations, however, came up and were reported on in her hypnosis.

Her condition improved on the whole. She took nourishment without difficulty and allowed the nurse to feed her; except that she asked for bread but rejected it the moment it touched her lips. The paralytic contracture of the leg diminished greatly. There was also an improvement in her power of judgement and she became much attached to my friend Dr. B., the physician who visited her. She derived much benefit from a Newfoundland dog which was given to her and of which she was passionately fond. On one occasion, though, her pet made an attack on a cat, and it was splendid to see the way in which the frail girl seized a whip in her left hand and beat off the huge beast with it to rescue his victim. Later, she looked after some poor, sick people, and this helped her greatly.

It was after I returned from a holiday trip which lasted several weeks that I received the most convincing evidence of the pathogenic and exciting effect brought about by the ideational complexes which were produced during her absences, or condition seconde, and of the fact that these complexes were disposed of by being given verbal expression during hypnosis. During this interval no ‘talking cure’ had been carried out, for it was impossible to persuade her to confide what she had to say to anyone but me - not even to Dr.

B. to whom she had in other respects become devoted. I found her in a wretched moral state, inert, unamenable, ill-tempered, even malicious. It became plain from her evening stories that her imaginative and poetic vein was drying up. What she reported was more and more concerned with her hallucinations and, for instance, the things that had annoyed her during the past days. These were clothed in imaginative shape, but were merely formulated in stereotyped images rather than elaborated into poetic productions. But the situation only became tolerable after I had arranged for the patient to be brought back to Vienna for a week and evening after evening made her tell me three to five stories. When I had accomplished this, everything that had accumulated during the weeks of my absence had been worked off. It was only now that the former rhythm was re-established: on the day after her giving verbal utterance to her phantasies she was amiable and cheerful, on the second day she was more irritable and less agreeable and on the third positively ‘nasty’. Her moral state was a function of the time that had elapsed since her last utterance. This was because every one of the spontaneous products of her imagination and every event which had been assimilated by the pathological part of her mind persisted as a psychical stimulus until it had been narrated in her hypnosis, after which it completely ceased to operate.

When, in the autumn, the patient returned to Vienna (though to a different house from the one in which she had fallen ill), her condition was bearable, both physically and mentally; for very few of her experiences

- in fact only her more striking ones - were made into psychical stimuli in a pathological manner. I was hoping for a continuous and increasing improvement, provided that the permanent burdening of her mind with fresh stimuli could be prevented by her giving regular verbal expression to them. But to begin with I was disappointed. In December there was a marked deterioration of her psychical condition. She once more became excited, gloomy and irritable. She had no more ‘really good days’ even when it was impossible to detect anything that was remaining ‘stuck’ inside her. To wards the end of December, at Christmas time, she was particularly restless, and for a whole week in the evenings she told me nothing new but only the imaginative products which she had elaborated under the stress of great anxiety and emotion during the Christmas of 1880. When the scenes had been completed she was greatly relieved.

A year had now passed since she had been separated from her father and had taken to her bed, and from this time on her condition became clearer and was systematized in a very peculiar manner. Her alternating states of consciousness, which were characterized by the fact that, from morning onwards, her absences (that is to say, the emergence of her condition seconde) always became more frequent as the day advanced and took entire possession by the evening - these alternating states had differed from each other previously in that one (the first) was normal and the second alienated; now, however, they differed further in that in the first she lived, like the rest of us, in the winter of 1881-2, whereas in the second she lived in the winter of 1880-1, and had completely forgotten all the subsequent events. The one thing that nevertheless seemed to remain conscious most of the time was the fact that her father had died. She was carried back to the previous year with such intensity that in the new house she hallucinated her old room, so that when she wanted to go to the door she knocked up against the stove which stood in the same relation to the window as the door did in the old room. The change-over from one state to another occurred spontaneously but could also be very easily brought about by any sense-impression which vividly recalled the previous year. One had only to hold up an orange before her eyes (oranges were what she had chiefly lived on during the first part of her illness) in order to carry her over from the year 1882 to the year 1881.

But this transfer into the past did not take place in a general or indefinite manner; she lived through the previous winter day by day. I should only have been able to suspect that this was happening, had it not been that every evening during the hypnosis she talked through whatever it was that had excited her on the same day in 1881, and had it not been that a private diary kept by her mother in 1881 confirmed beyond a doubt the occurrence of the underlying events. This re-living of the previous year continued till the illness came to its final close in June, 1882.

It was interesting here, too, to observe the way in which these revived psychical stimuli belonging to her secondary state made their way over into her first, more normal one. It happened, for instance, that one morning the patient said to me laughingly that she had no idea what was the matter but she was angry with me. Thanks to the diary I knew what was happening; and, sure enough, this was gone through again in the evening hypnosis: I had annoyed the patient very much on the same evening in 1881. Or another time she told me there was something the matter with her eyes; she was seeing colours wrong. She knew she was wearing a brown dress but she saw it as a blue one. We soon found that she could distinguish all the colours of the visual test-sheets correctly and clearly, and that the disturbance only related to the dress- material. The reason was that during the same period in 1881 she had been very busy with a dressing- gown for her father, which was made with the same material as her present dress, but was blue instead of brown. Incidentally, it was often to be seen that these emergent memories showed their effect in advance; the disturbance of her normal state would occur earlier on, and the memory would only gradually be awakened in her condition seconde.

Her evening hypnosis was thus heavily burdened, for we had to talk off not only her contemporary imaginative products but also the events and ‘vexations’¹ of 1881. (Fortunately I had already relieved her at the time of the imaginative products of that year.) But in addition to all this the work that had to be done by the patient and her physician was immensely increased by a third group of separate disturbances which had to be disposed of in the same manner. These were the psychical events involved in the period of incubation of the illness between July and December, 1880; it was they that had produced the whole of the hysterical phenomena, and when they were brought to verbal utterance the symptoms disappeared.

When this happened for the first time - when, as a result of an accidental and spontaneous utterance of this kind, during the evening hypnosis, a disturbance which had persisted for a considerable time vanished

- I was greatly surprised. It was in the summer during a period of extreme heat, and the patient was suffering very badly from thirst; for, without being able to account for it in any way, she suddenly found it impossible to drink. She would take up the glass of water she longed for, but as soon as it touched her lips she would push it away like some one suffering from hydrophobia. As she did this, she was obviously in an absence for a couple of seconds. She lived only on fruit, such as melons, etc., so as to lessen her tormenting thirst. This had lasted for some six weeks, when one day during hypnosis she grumbled about her English lady-companion whom she did not care for, and went on to describe, with every sign of disgust, how she had once gone into that lady’s room and how her little dog - horrid creature! - had drunk out of a glass there. The patient had said nothing, as she had wanted to be polite. After giving further energetic expression to the anger she had held back, she asked for something to drink, drank a large quantity of water without any difficulty and woke from her hypnosis with the glass at her lips; and thereupon the disturbance vanished, never to return. A number of extremely obstinate whims were similarly removed after she had described the experiences which had given rise to them. She took a great step forward when the first of her chronic symptoms disappeared in the same way - the contracture of her right leg, which, it is true, had already diminished a great deal. These findings - that in the case of this patient the hysterical phenomena disappeared as soon as the event which had given rise to them was reproduced in her hypnosis - made it possible to arrive at a therapeutic technical procedure which left nothing to be desired in its logical consistency and systematic application. Each individual symptom in this complicated case was taken separately in hand; all the occasions on which it had appeared were described in reverse order, starting before the time when the patient became bed-ridden and going back to the event which had led to its first appearance. When this had been described the symptom was permanently removed.

¹ [In English in the original.]

In this way her paralytic contractures and anaesthesias, disorders of vision and hearing of every sort, neuralgias, coughing, tremors, etc., and finally her disturbances of speech were ‘talked away’. Amongst the disorders of vision, the following, for instance, were disposed of separately: the convergent squint with diplopia; deviation of both eyes to the right, so that when her hand reached out for something it always went to the left of the object; restriction of the visual field; central amblyopia; macropsia; seeing a death’s head instead of her father; inability to read. Only a few scattered phenomena (such, for instance, as the extension of the paralytic contractures to the left side of her body) which had developed while she was confined to bed, were untouched by this process of analysis, and it is probable, indeed, that they in fact had no immediate physical cause.

It turned out to be quite impracticable to shorten the work by trying to elicit in her memory straight away the first provoking cause of her symptoms. She was unable to find it, grew confused, and things proceeded even more slowly than if she was allowed quietly and steadily to follow back the thread of memories on which she had embarked. Since the latter method, however, took too long in the evening hypnosis, owing to her being over-strained and distraught by ‘talking out’ the two other sets of experiences - and owing, too, to the reminiscences needing time before they could attain sufficient vividness - we evolved the following procedure. I used to visit her in the morning and hypnotize her. (Very simple methods of doing this were arrived at empirically.) I would next ask her to concentrate her thoughts on the symptom we were treating at the moment and to tell me the occasions on which it had appeared. The patient would proceed to describe in rapid succession and under brief headings the external events concerned and these I would jot down.

During her subsequent evening hypnosis she would then, with the help of my notes, give me a fairly detailed account of these circumstances.

An example will show the exhaustive manner in which she accomplished this. It was our regular experience that the patient did not hear when she was spoken to. It was possible to differentiate this passing habit of not hearing as follows:

(a) Not hearing when someone came in, while her thoughts were abstracted. 108 separate detailed instances of this, mentioning the persons and circumstances, often with dates. First instance: not hearing her father come in.

(b) Not understanding when several people were talking. 27 instances. First instance: her father, once more, and an acquaintance.

(c) Not hearing when she was alone and directly addressed. 50 instances. Origin: her father having vainly asked her for some wine.

(d) Deafness brought on by being shaken (in a carriage, etc.). 15 instances. Origin: having been shaken angrily by her young brother when he caught her one night listening at the sick room door.

(e) Deafness brought on by fright at a noise. 37 instances. Origin: a choking fit of her father’s, caused by swallowing the wrong way.

(f) Deafness during deep absence. 12 instances.

(g) Deafness brought on by listening hard for a long time, so that when she was spoken to she failed to hear. 54 instances.

Of course all these episodes were to a great extent identical in so far as they could be traced back to states of abstraction or absences or to fright. But in the patient’s memory they were so clearly differentiated, that if she happened to make a mistake in their sequence she would be obliged to correct herself and put them in the right order; if this was not done her report came to a standstill. The events she described were so lacking in interest and significance and were told in such detail that there could be no suspicion of their having been invented. Many of these incidents consisted of purely internal experiences and so could not be verified; others of them (or circumstances attending them) were within the recollection of people in her environment.

This example, too, exhibited a feature that was always observable when a symptom was being ‘talked away’: the particular symptom emerged with greater force while she was discussing it. Thus during the analysis of her not being able to hear she was so deaf that for part of the time I was obliged to communicate with her in writing. The first provoking cause was habitually a fright of some kind, experienced while she was nursing her father - some oversight on her part, for instance.

The work of remembering was not always an easy matter and sometimes the patient had to make great efforts. On one occasion our whole progress was obstructed for some time because a recollection refused to emerge. It was a question of a particularly terrifying hallucination. While she was nursing her father she had seen him with a death’s head. She and the people with her remembered that once, while she still appeared to be in good health, she had paid a visit to one of her relatives. She had opened the door and all at once fallen down unconscious. In order to get over the obstruction to our progress she visited the same place again and, on entering the room, again fell to the ground unconscious. During her subsequent evening hypnosis the obstacle was surmounted. As she came into the room, she had seen her pale face reflected in a mirror hanging opposite the door; but it was not herself that she saw but her father with a death’s head. - We often noticed that her dread if a memory, as in the present instance, inhibited its emergence, and this had to be brought about forcibly by the patient or physician.

The following incident, among others, illustrates the high degree of logical consistency of her states. During this period, as has already been explained, the patient was always in her condition seconde - that is, in the year 1881 - at night. On one occasion she woke up during the night, declaring that she had been taken away from home once again, and became so seriously excited that the whole household was alarmed. The reason was simple. During the previous evening the talking cure had cleared up her disorder of vision, and this applied also to her condition seconde. Thus when she woke up in the night she found herself in a strange room, for her family had moved house in the spring of 1881. Disagreeable events of this kind were avoided by my always (at her request) shutting her eyes in the evening and giving her a suggestion that she would not be able to open them till I did so myself on the following morning. The disturbance was only repeated once, when the patient cried in a dream and opened her eyes on waking up from it.

Since this laborious analysis for her symptoms dealt with the summer months of 1880, which was the preparatory period of her illness, I obtained complete insight into the incubation and pathogenesis of this case of hysteria, and I will now describe them briefly.

In July, 1880, while he was in the country, her father fell seriously ill of a sub-pleural abscess. Anna shared the duties of nursing him with her mother. She once woke up during the night in great anxiety about the patient, who was in a high fever; and she was under the strain of expecting the arrival of a surgeon from Vienna who was to operate. Her mother had gone away for a short time and Anna was sitting at the bedside with her right arm over the back of her chair. She fell into a waking dream and saw a black snake coming towards the sick man from the wall to bite him. (It is most likely that there were in fact snakes in the field behind the house and that these had previously given the girl a fright; they would thus have provided the material for her hallucination.) She tried to keep the snake off, but it was as though she was paralysed. Her right arm, over the back of the chair, had gone to sleep and had become anaesthetic and paretic; and when she looked at it the fingers turned into little snakes with death’s heads (the nails). (It seems probable that she had tried to use her paralysed right arm to drive off the snake and that its anaesthesia and paralysis had consequently become associated with the hallucination of the snake.) When the snake vanished, in her terror she tried to pray. But language failed her: she could find no tongue in which to speak, till at last she thought of some children’s verses in English and then found herself able to think and pray in that language. The whistle of the train that was bringing the doctor whom she expected broke the spell.

Next day, in the course of a game, she threw a quoit into some bushes; and when she went to pick it out, a bent branch revived her hallucination of the snake, and simultaneously her right arm became rigidly extended. Thenceforward the same thing invariably occurred whenever the hallucination was recalled by some object with a more or less snake-like appearance. This hallucination, however, as well as the contracture only appeared during the short absences which became more and more frequent from that night onwards. (The contracture did not become stabilized until December, when the patient broke down completely and took to her bed permanently.) As a result of some particular event which I cannot find recorded in my notes and which I no longer recall, the contracture of the right leg was added to that of the right arm.

Her tendency to auto-hypnotic absences was from now on established. On the morning after the night I have described, while she was waiting for the surgeon’s arrival, she fell into such a fit of abstraction that he finally arrived in the room without her having heard his approach. Her persistent anxiety interfered with her eating and gradually led to intense feelings of nausea. Apart from this, indeed, each of her hysterical symptoms arose during an affect. It is not quite certain whether in every case a momentary state of absence was involved, but this seems probable in view of the fact that in her waking state the patient was totally unaware of what had been going on.

Some of her symptoms, however, seem not to have emerged in her absences but merely in an affect during her waking life; but if so, they recurred in just the same way. Thus we were able to trace back all of her different disturbances of vision to different, more or less clearly determining causes. For instance, on one occasion, when she was sitting by her father’s bedside with tears in her eyes, he suddenly asked her what time it was. She could not see clearly; she made a great effort, and brought her watch near to her eyes. The face of the watch now seemed very big - thus accounting for her macropsia and convergent squint. Or again, she tried hard to suppress her tears so that the sick man should not see them.

A dispute, in the course of which she suppressed a rejoinder, caused a spasm of the glottis, and this was repeated on every similar occasion.

She lost the power of speech (a) as a result of fear, after her first hallucination at night, (b) after having suppressed a remark another time (by active inhibition), (c) after having been unjustly blamed for something and (d) on every analogous occasion (when she felt mortified). She began coughing for the first time when once, as she was sitting at her father’s bedside, she heard the sound of dance music coming from a neighbouring house, felt a sudden wish to be there, and was overcome with self-reproaches.

Thereafter, throughout the whole length of her illness she reacted to any markedly rhythmical music with a

tussis nervosa.

I cannot feel much regret that the incompleteness of my notes makes it impossible for me to enumerate all the occasions on which her various hysterical symptoms appeared. She herself told me them in every single case, with the one exception I have mentioned; and, as I have already said, each symptom disappeared after she had described its first occurrence.

In this way, too, the whole illness was brought to a close. The patient herself had formed a strong determination that the whole treatment should be finished by the anniversary of the day on which she was moved into the country. At the beginning of June, accordingly, she entered into the ‘talking cure’ with the greatest energy. On the last day - by the help of re-arranging the room so as to resemble her father’s sickroom - she reproduced the terrifying hallucination which I have described above and which constituted the root of her whole illness. During the original scene she had only been able to think and pray in English; but immediately after its reproduction she was able to speak German. She was moreover free from the innumerable disturbances which she had previously exhibited. After this she left Vienna and travelled for a while; but it was a considerable time before she regained her mental balance entirely. Since then she has enjoyed complete health.

Although I have suppressed a large number of quite interesting details, this case history of Anna O. has grown bulkier than would seem to be required for a hysterical illness that was not in itself of an unusual character. It was, however, impossible to describe the case without entering into details, and its features seem to me of sufficient importance to excuse this extensive report. In just the same way, the eggs of the echinoderm are important in embryology, not because the sea urchin is a particularly interesting animal but because the protoplasm of its eggs is transparent and because what we observe in them thus throws light on the probable course of events in eggs whose protoplasm is opaque. The interest of the present case seems to me above all to reside in the extreme clarity and intelligibility of its pathogenesis.

There were two psychical characteristics present in the girl while she was still completely healthy which acted as predisposing causes for her subsequent hysterical illness:

(1) Her monotonous family life and the absence of adequate intellectual occupation left her with an unemployed surplus of mental liveliness and energy, and this found an outlet in the constant activity of her imagination.

(2) This led to a habit of day-dreaming (her ‘private theatre’), which laid the foundations for a dissociation of her mental personality. Nevertheless a dissociation of this degree is still within the bounds of normality. Reveries and reflections during a more or less mechanical occupation do not in themselves imply a pathological splitting of consciousness, since if they are interrupted - if, for instance, the subject is spoken to - the normal unity of consciousness is restored; nor, presumably, is any amnesia present. In the case of Anna O., however, this habit prepared the ground upon which the affect of anxiety and dread was able to establish itself in the way I have described, when once that affect had transformed the patient’s habitual day-dreaming into a hallucinatory absence. It is remarkable how completely the earliest manifestation of her illness in its beginnings already exhibited its main characteristics, which afterwards remained unchanged for almost two years. These comprised the existence of a second state of consciousness which first emerged as a temporary absence and later became organized into a ‘double conscience’; an inhibition of speech, determined by the affect of anxiety, which found a chance discharge in the English verses; later on, paraphasia and loss of her mother-tongue, which was replaced by excellent English; and lastly the accidental paralysis of her right arm, due to pressure, which later developed into a contractural paresis and anaesthesia on her right side. The mechanism by which this latter affection came into being agreed entirely with Charcot’s theory of traumatic hysteria - a slight trauma occurring during a state of hypnosis.

But whereas the paralysis experimentally provoked by Charcot in his patients became stabilized immediately, and whereas the paralysis caused in sufferers from traumatic neuroses by a severe traumatic shock sets in at once, the nervous system of this girl put up a successful resistance for four months. Her contracture, as well as the other disturbances which accompanied it set in only during the short absences in her condition seconde, and left her during her normal state in full control of her body and possession of her senses; so that nothing was noticed either by herself or by those around her, though it is true that the attention of the latter was centred upon the patient’s sick father and was consequently diverted from her.

Since, however, her absences with their total amnesia and accompanying hysterical phenomena grew more and more frequent from the time of her first hallucinatory auto-hypnosis, the opportunities multiplied for the formation of new symptoms of the same kind, and those that had already been formed became more strongly entrenched by frequent repetition. In addition to this, it gradually came about that any sudden distressing affect would have the same result as an absence (though, indeed, it is possible that such affects actually caused a temporary absence in every case); chance coincidences set up pathological associations and sensory or motor disturbances, which thenceforward appeared along with the affect. But hitherto this only occurred for fleeting moments. Before the patient took permanently to her bed she had already developed the whole assemblage of hysterical phenomena, without anyone knowing it. It was only after the patient had broken down completely owing to exhaustion brought about by lack of nourishment, insomnia and constant anxiety, and only after she had begun to pass more time in her condition seconde than in her normal state, that the hysterical phenomena extended to the latter as well and changed from intermittent acute symptoms into chronic ones.

The question now arises how far the patient’s statements are to be trusted and whether the occasions and mode of origin of the phenomena were really as she represented them. So far as the more important and fundamental events are concerned, the trustworthiness of her account seems to me to be beyond question. As regards the symptoms disappearing after being ‘talked away’, I cannot use this as evidence; it may very well be explained by suggestion. But I always found the patient entirely truthful and trustworthy. The things she told me were intimately bound up with what was most sacred to her. Whatever could be checked by other people was fully confirmed. Even the most highly gifted girl would be incapable of concocting a tissue of data with such a degree of internal consistency as was exhibited in the history of this case. It cannot be disputed, however, that precisely her consistency may have led her (in perfectly good faith) to assign to some of her symptoms a precipitating cause which they did not in fact possess. But this suspicion, too, I consider unjustified. The very insignificance of so many of those causes, the irrational character of so many of the connections involved, argue in favour of their reality. The patient could not understand how it was that dance music made her cough; such a construction is too meaningless to have been deliberate. (It seemed very likely to me, incidentally, that each of her twinges of conscience brought on one of her regular spasms of the glottis and that the motor impulses which she felt - for she was very fond of dancing - transformed the spasm into a tussis nervosa.) Accordingly, in my view the patient’s statements were entirely trustworthy and corresponded to the facts.

And now we must consider how far it is justifiable to suppose that hysteria is produced in an analogous way in other patients, and that the process is similar where no such clearly distinct condition seconde has become organized. I may advance in support of this view the fact that in the present case, too, the story of the development of the illness would have remained completely unknown alike to the patient and the physician if it had not been for her peculiarity of remembering things in hypnosis, as I have described, and of relating what she remembered. While she was in her waking state she knew nothing of all this. Thus it is impossible to arrive at what is happening in other cases from an examination of the patients while in a waking state, for with the best will in the world they can give one no information. And I have already pointed out how little those surrounding the present patient were able to observe of what was going on.

Accordingly, it would only be possible to discover the state of affairs in other patients by means of some such procedure as was provided in the case of Anna O. by her auto-hypnoses. Provisionally we can only express the view that trains of events similar to those here described occur more commonly than our ignorance of the pathogenic mechanism concerned has led us to suppose.

When the patient had become confined to her bed, and her consciousness was constantly oscillating between her normal and her ‘secondary’ state, the whole host of hysterical symptoms, which had arisen separately and had hitherto been latent, became manifest, as we have already seen, as chronic symptoms. There was now added to these a new group of phenomena which seemed to have had a different origin: the paralytic contractures of her left extremities and the paresis of the muscles raising her head. I distinguish them from the other phenomena because when once they had disappeared they never returned, even in the briefest or mildest form or during the concluding and recuperative phase, when all the other symptoms became active again after having been in abeyance for some time. In the same way, they never came up in the hypnotic analyses and were not traced back to emotional or imaginative sources. I am therefore inclined to think that their appearance was not due to the same psychical process as was that of the other symptoms, but is to be attributed to a secondary extension of that unknown condition which constitutes the somatic foundation of hysterical phenomena.

Throughout the entire illness her two states of consciousness persisted side by side: the primary one in which she was quite normal psychically, and the secondary one which may well be likened to a dream in view of its wealth of imaginative products and hallucinations, its large gaps of memory and the lack of inhibition and control in its associations. In this secondary state the patient was in a condition of alienation. The fact that the patient’s mental condition was entirely dependent on the intrusion of this secondary state into the normal one seems to throw considerable light on at least one class of hysterical psychosis. Every one of her hypnoses in the evening afforded evidence that the patient was entirely clear and well-ordered in her mind and normal as regards her feeling and volition so long as none of the products of her secondary state was acting as a stimulus ‘in the unconscious’. The extremely marked psychosis which appeared whenever there was any considerable interval in this unburdening process showed the degree to which those products influenced the psychical events of her ‘normal’ state. It is hard to avoid expressing the situation by saying that the patient was split into two personalities of which one was mentally normal and the other insane. The sharp division between the two states in the present patient only exhibits more clearly, in my opinion, what has given rise to a number of unexplained problems in many other hysterical patients. It was especially noticeable in Anna O. how much the products of her ‘bad self’, as she herself called it, affected her moral habit of mind. If these products had not been continually disposed of, we should have been faced by a hysteric of the malicious type - refractory, lazy, disagreeable and ill-natured; but, as it was, after the removal of those stimuli her true character, which was the opposite of all these, always reappeared at once.

Nevertheless, though her two states were thus sharply separated, not only did the secondary state intrude into the first one, but - and this was at all events frequently true, and even when she was in a very bad condition - a clear-sighted and calm observer sat, as she put it, in a corner of her brain and looked on at all the mad business. This persistence of clear thinking while the psychosis was actually going on found expression in a very curious way. At a time when, after the hysterical phenomena had ceased, the patient was passing through a temporary depression, she brought up a number of childish fears and self- reproaches, and among them the idea that she had not been ill at all and that the whole business had been simulated. Similar observations, as we know, have frequently been made. When a disorder of this kind has cleared up and the two states of consciousness have once more become merged into one, the patients, looking back to the past, see themselves as the single undivided personality which was aware of all the nonsense; they think they could have prevented it if they had wanted to, and thus they feel as though they had done all the mischief deliberately. - It should be added that this normal thinking which persisted during the secondary state must have fluctuated enormously in its amount and must very often have been completely absent.

I have already described the astonishing fact that from beginning to end of the illness all the stimuli arising from the secondary state, together with their consequences, were permanently removed by being given verbal utterance in hypnosis, and I have only to add an assurance that this was not an invention of mine which I imposed on the patient by suggestion. It took me completely by surprise, and not until symptoms had been got rid of in this way in a whole series of instances did I develop a therapeutic technique out of it.

The final cure of the hysteria deserves a few more words. It was accompanied, as I have already said, by considerable disturbances and a deterioration in the patient’s mental condition. I had a very strong impression that the numerous products of her secondary state which had been quiescent were now forcing their way into consciousness; and though in the first instance they were being remembered only in her secondary state, they were nevertheless burdening and disturbing her normal one. It remains to be seen whether it may not be that the same origin is to be traced in other cases in which a chronic hysteria terminates in a psychosis.